One can make sense of the overall context of 20th century including Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Derrida with the help of adopting a notion on which all of these philosophers agree to have taken as their subject matter of inquiry; namely, overcoming of the traditional Western metaphysics. Although three of them adopt distinct paths for doing so, as they belong to different orientations of philosophy‒of hermeneutic, of analytical, and of postmodern orientation respectively‒shaped the perspective from which they make judgments about the concept of “traditional Western Metaphysics”, they share some common grounds and borrowed several notions from one another in dealing with the issue‒some of which are extremely useful for one to understand the continuum of this epoch of philosophy better. In this paper, I will first clarify what does Derrida means when he talks about metaphysics, in comparison with mainly Heidegger’s understanding of metaphysics and with Nietzschean way of philosphyzing‒although this issue is a point of huge debate for them as well as still in our time‒by emphasizing the relations between their most important notions which help Derrida when building his strategy of deconstruction as a non-metaphysical way of approaching a text and of philosophyzing. Then, I will introduce his alternative of post-metaphysical philosophyzing, namely the strategy of deconstruction, and the relation of this alternative to the posterior generation of philosophyzing in Western tradition, “traditional metaphysics” as they attribute. At the end, I will talk about the Derrida’s reading of Plato’s dialogue, Phaedrus, as well as his reading of Rousseau with a minor emphasis, as instances‒all of which are helpful to make notions previously introduced abstractly more concrete and contextual‒ where he employs his strategy of deconstruction. At last, I will try to reach a conclusion on the validity of Derrida’s strategy of deconstruction as a way of post-metaphysical philosophyzing, in terms of both alternative approaches and its position towards the traditional Western metaphysics as an epoch of departure, and as an epoch to be “triumphed over”.

In Derrida’s conceptualizing, the word “metaphysics” is used as an abbreviation for any science of presence, and it is closely related to the logocentricism, phonocentrisim, ethnocentricism, as well as phallocentricism‒in that all of which are the neologistic notions which Derrida accuses of having developed as a result of metaphysics as way of putting notions into binary opposites while privileging the one in sacrifice of the other. This is regarded as a huge metaphysical presupposition for Derrida, which is important as he objects the theses that the meaning can be achieved in commiting oneself to the temporality privileging present, but he has a different theory of composition of meaning in which the absence plays a crucial role as well. For Derrida, the pure presence itself, if possible, amounts to death; thus, it can explicate nothing regarding the acquisition of meaning from a text‒from a composition of signs. In his words, the science he tries to establish to give intelligible linguistic and philosophical accounts for these posited binaries, i.e. grammatology, treats metaphysics as “the history of determination of being as presence”[1]. Metaphysics of presence states in its most general sense that the truth, that is the eternal logos itself, is eternal; yet, in terms of the temporal existence of human beings is concerned, the truth can only manifest itself as presence.

Upon considering only his rejection of metaphysics regarding temporality, one can see the influence as well as the inevitable references to Heidegger who challenged the notion of what he conceptualizes as “vulgar conception of time”, meaning the conception of time prevailing the history of philosophy from Aristotle onwards, comprehending time as a “moving now/the present moment” and by doing so privileging the present instances over the future as a temporal state. To give maybe the most extreme example of this conceptualization of presence from a Neo-Platonist Boethius (480-524), in the onto-theological epoch of philosophy as Derrida names it, Boethius, while reconciling the free will and the divine foreknowledge (this would be the transcendental signifier for Derrida), claimed that as God is an eternal being, his knowledge is so as well meaning that he does not experience the time as three temporal states of past-present-future, but he experiences it as a moving-now which is the expression of his eternality. This understanding of the world leaves no grounds for understanding how signs as composed of signifiers and signified come to existence and relate to one another to achieve the meaning; because, the whole burden to carry the meaning is left to a privileged sign, the “timeless” God, which one cannot be put in direct relation to our worldly signs making the composition of meaning and acquisition of the alleged “Truth” unintelligible. The meaning of Being or Dasein is, for Heidegger, finds itself in the temporality; yet, it is not a temporality as it is conceptualized in the above lines. Rather, the radical difference is his prioritizing the future against the present. For Heidegger, the Dasein projects itself to the future and can be said to exist only on the condition that it considers future possibilities/contingencies as prior to what is present to itself. The temporality is understood as a time horizon rather than a present point. This radical break with the metaphysics of presence is crucial for Derrida to conceptualize his critique of metaphysics. Also Derrida borrows from Heidegger’s conception of “destructive retrieve”[2], that is to make use of the notions of an old epoch of philosophy one tries to overcome, yet as one objects the older usage of the notions one uses, he merely put a cross over the word by making it legible still, because there is no word to use instead (It can also be expressed as challenging the tradition not immediately by destructing it but by borrowing notions from it to explicate both their link and their difference. For example, Heidegger continues to use word Being, an older metaphysical notion for Dasein, by crossing it over.). The concept of “deconstructive retrieve” will be relevant when I will introduce the two distinct stages of Derrida’s strategy of deconstruction. Lastly, for me, the conception of truth as explicated by Heidegger as “Aletheia” (disclosure of partial references to compose a meaning) is also relevant for Derrida; because, Derrida, as well, talks not in the context of pure truth and falsity anymore, but in the context of interpretation and composing a subjective meaning.

Related to comparison, the evaluation of Nietzsche in this context needs to be made according to me, it is actually as important as Heidegger’s influence, especially when Derrida’s particular way of philosophizing as a process-like fashion is concerned. Although Heidegger thinks that Nietzsche remained simply in the domain of metaphysics[3] by declaring him infamously as the last of all metaphysicians, Derrida never accepts this view. For him, Nietzsche goes far beyond the borders of metaphysics with his notion of eternal recurrence, which is a notion regarding the ethical development of a human being where the human being reaches the highest and most valuable stage in which he wills the eternal repetition of an instance in his life depicting a sort of amor fati. This Nietzschean affirmation for Derrida, can liberate “the signifier from its dependence or derivation with respect to the logos and the related concept of truth or the primary signified,”[4] because of the fact that Nietzsche as well, in his groundbreaking, vitalist way of philosophizing, relates the sings never to an external and sacred reference point. Yet, for me, it is obscure that, while Derrida stands up for Nietzsche so willingly, whether he ever considered Nietzsche’s development of values and meanings in an autopoietic system‒as far as Nietzsche’s account allows for a system in this sense, and seemingly it is with its dependence on naturalistic notion of “will to power” and vitalism‒in which those values are created without reference to outside systems directly but in a close and natural relation to one-another with the notion of “will to power” reconcilable with the deconstuctable systems of his usual considerations.

Moving on to the affects of the traditional conceptualizing of metaphysics as prioritizing the present, on the notion of sign is helpful to understand the logocentric and phonologist structure of language shaped with this understanding of metaphysics, and to comprehend that in this context it is impossible to create and communicate with meanings with neither phonic nor graphic signs. For Aristotle, the spoken words are immediate reflections of our intelligible mental states, thus being the direct and the most accurate signs of those states. Yet, the written words for him only the signs of signs (of the spoken words) and that they are far away from the reality. In the Of Grammatology, as well, Derrida criticizes Saussure for his privileging the speech over writing, the phonologism descending from the same roots as metaphysics of presence for Derrida. He also claims that, “the linguistics remains a metaphysics as long as it retains the distinction between signified and signifier within the concept of the sign.”[5]. One can argue that the alleged intelligibility of the phonic signs, i.e. speech, over that of the writing is grounded on the epistemological and ontological commitment to an absolute logos. This commitment is external to the interactions of the signs themselves, making “the absolute logos” a privileged signifier. The problem with this perspective, for Derrida, is that one cannot account for creation of meaning or communication with signs once one liberates oneself from the metaphysics of presence and justifies himself for doing this (as Derrida justifies himself by claiming that it is not the case that all along the communication of the meaning, the presence of a signifier or a referrer to be present, but one needs to consider the case of absence such as suicide letters read in the absence of the agent who writes them. Also in his picture where all signs depend one-another, there is no realm of immediacy that has authority to prioritize the direct reference to that alleged immediacy.). Thus, the fact that one can only find this time deferrals regarding the existence of the signifier and the referrer, in the case of writing‒not in the case of speech where it is always the case that the speaker is present‒Derrida’s project is focused on this that-far marginalized activity of language: “writing”. At this point, “mediations upon writing and the deconstruction of philosophy become inseparable.”[6].

The strategy of deconstruction, a notion regarding linguistics and philosophy which enables one to reflect upon the binary oppositions posited with flawed presuppositions, and to break links with logocentrically and phonocentrically (as well as ethnocentric and phallocentric, yet they are not the main issue of consideration here) oriented understanding of meaning, which is not capable of providing intelligible meaning in reality. The strategy of deconstruction as a way of post-metaphysical philosophyzing focuses on mainly the exposure of the binary oppositions in a given text in the first place namely the overturning the significance of the opposition from the privileged side of the one to the marginalized notion (such as by showing that for speech to be more important with respect to writing, the writing must have a significance at least as much as speech), and in the second place subverting those oppositions, challenging their authority derived from the metaphysics of presence itself. Derrida’s conception of “writing” is not the ordinary writing that one is exposed to in ordinary books, but rather can be expressed with his neologism “arche-writing” that includes infinite referral (like Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence) and seeking the meaning in the infinite chains of signs without referring non-signs. Arche-writing includes the spatial-differing (one may write for someone to read in another place at another time without need to know the author himself to get an interpretation of it) and the temporal deferring (meaning of a certain text is never “present” at hand for the reader to adopt immediately, yet it requires reader to involve the binary operations of the text himself; in a Heideggerian sense text’s meanings “project itself into the context of its future readers”.). Regarding this notion of arche-writing, Derrida coins yet another term “différance” (which is a combination of both words “differ” and “deffer”, and pronounced same as the original French word “difference”, thus making the reference to the writing necessary), and he defines it as “the typical of what is involved in arche-writing and this generalized notion of writing that breaks down the entire logic of the sign…neither a word nor a concept.”[7]. Notions of difference and trace of Derrida leads one where to focus on while deconstructing a text. While one examines the binary oppositions in a text during a procedure of deconstruction, one tries to find ways to expose a trace to free oneself from the borders of metaphysics. Because, in traditional metaphysics, trace does not determined as such, but in a text by way of investigating grammatical structures that iterates (“pharmakon” in Plato’s dialogue Pheaedrus), also the ones that are seemingly absent but necessarily referred by the trace (“pharmakos” in Plato’s Phaedrus– the reason why metaphysics cannot account for trace lies here that it cannot account for a notion that is absent yet still referred and affects the meaning of the text.). Then if the following through the trace we find in the text is the way to get the meaning out of it, one can interpret Derrida’s slogan-like, famous claim, “There is nothing outside of text,” by taking the meaning of the “text” not as books etc. but as Spivak in his Preface to Of Grammatology mentions, by taking the meaning of a text “whether ‘literary’, ‘psychic’, ‘anthropological’ or otherwise, a play of presence and absence, a place of the effaced trace.”[8]. One can easily affirm that the notion of trace is not linguistic, making one then agree that his notion of “text” is not merely linguistic itself, but a huge fabric of traces interrelated to one-another.

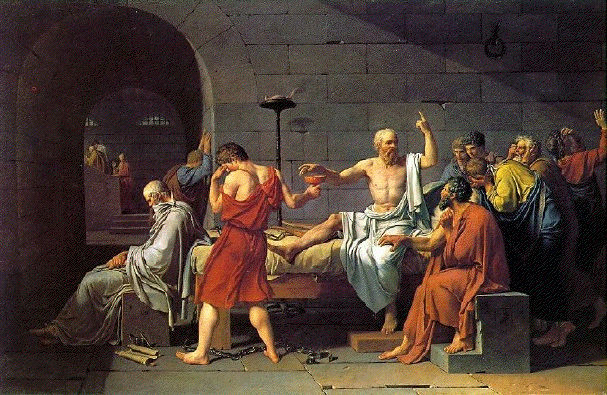

Lastly, Derrida’s deconstructive reading of Rousseau and Plato’s Phaedrus dialogue will be considered. Derrida, in Of Grammatology, tries to challenge Rousseau’s natural state argument’s one instance, namely that in natural state man only possess speech and the adittion of writing merely brings corruption to the world, a rupture from its innocent immediate state directly related to nature. While Derrida argues for the culture/nature binary opposition while following the trace of the repeated word in Rousseau, “supplement” (i.e. the writing’s being mere supplement to the speech); in Plato’s Pharmacy, he directly deconstructs the binary opposition of writing/speech in the text by Plato, affirmed as the first metaphysician as Derrida conceptualizes metaphysics, named Phaedrus. In the dialogue, seemingly having its focus on the conception of love and beauty centrally (and many editions title it as “Phaedrus or On Beauty”), Socrates insists Phaedrus who is coming from his friend Lysias, a famous speaker, to read himself the written text that Phadrus carry with himself on which the Lysias’s speech on love is written. Lysias argues for showing affection for the ones that do not love you is more reasonable than to show it towards the ones in love with you in a qualified and educated manner. It is interesting, also Derrida realizes, that in the first part of the dialogue when Socrates sees the written text in the pocket of Phaedrus, he is almost seduced by the existence of the text, which leads him follow Phaedrus to the jungle with constantly expressing his emotional excitement in a distinguishable manner. Derrida emphasizes the marginalized nature of writing here. Yet, Socrates claims the writing is a corrupt way of expression because the unnecessary repetitions show the reader as if he talks about a substantial content but in fact he talks about simple matters. The iterabilitiy of the same words in writing, though, is what Derrida appreciates the writing for because for him this repeatibility means the writing’s ability to be read independent of outside authorities, even the writer‒unlike speech necessitating the speaker. Socrates, then, talks about the Egyptian god of writing (as well as magic, wisdom, knowledge of hieroglyphs to be emphasized) Thoth, who proposes the King his invent of writing as a remedy (“pharmakon” menaing bothe remedy and poison actually) for memory; yet, king rejects immediately to adopt it in society because he claims that writing can only a way of forgetting. Derrida claims that the King rejects the writing because he does not want his power authority coming from speech to be challenged by others. Derrida also leads us through the trace of three words coming from the same root by mediating on the roots of each in detail as he finds it necessary for deconstruction (like Nietzschean genealogical investigations). Althogh the words “pharmakeia”, “pharmakeus”, “pharmakon” are employed in Plato’s text; he does not use the word “pharmakos” (i.e. it is absent), though this absence for Derrida does not matter, as for him it is as present as the others on the grounds of his temporal assumptions. From following this trace of the words above, Derrida manages to challenge the opposition of writing/speech, because the “pharmakos” is an Ancient Greek notion of ritualistic sacrifice by sorcerers of a human “scapegoat”. This meaning refers that when the “pharmakon” of writing is rejected by the king, he in fact, though not made explicit in the text, declares writing to be the “scapegoat” and marginalized it; this realization challenged his alleged objective grounds for putting the speech and writing in binary oppositions.

To conclude Derrida’s conceptualizing the traditional Western metaphysics and his solution to overcome it, namely the strategy of deconstruction as a way of philosophizing after metaphysics, is a valid consideration for it refers internally to the “texts” and gets the appropriate meaning from within the text itself without reference to the outside authorities, to express his position modestly. In a way, I find his position more legitimate from the considerations of logical positivists in a way he develops his own language of writing from the text itself, and it is more intelligible than to posit an artificial language from outside to unify the meaning by taking its dependence to the outside domains. The reason why I raise the issue of logical positivists here is that his attempts while emphasizing the writing within the form of graphic signifiers are related to the founding of scientificity and historicity as claimed by him[9], which is not a completely distinct aim of logical positivists. Thus this last claim I give becomes the necessary “iteration” of the claim I have given in the introduction to this paper, namely that in the 20th century, the orientations that tries to overcome metaphysics are in continual and inevitable exchange with one another.

Bibliography

Derrida, Jacques. (1997) Of Grammatology, translated by Gayatri Chakrovarty Spivak, Baltimore: The John Hophins University.

Derrida, Jacques. (1981) Dissemination, translated with an introduction and additional notes By Barbara Johnson, London: The Athlone Press.

Kamut, Peggy, edited by. (1991) A Derrida Reader Between the Blinds, Columbia University Press.

Plato. (1943) Phaidros (Turkish spelling of “Phaedros”), İstanbul: Maarif Matbaası.

Reynolds, Jack. (Date of publish not specified.) “Jacques Derrida” Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/derrida/.

[1] Derrida (1997, p. 97).

[2] Reynolds argues for this interchange in his entry on Derrida on the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosphy.

[3] Kamut (1991, p. 34).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, p. 32.

[6] Derrida (1997, p. 86).

[7] Reynolds.

[8] Derrida (1997, from the Preface by Spivak).

[9] Ibid, p. 26. Derrida says that “Writing is the necessary condition of the possibility of ideal objects. Historicity and scientificity are possible only due to writing or the science of writing.”.